Article Directory

The Internal Revenue Service is about to run a massive, nationwide experiment in forced modernization. Under Executive Order 14247, the era of the paper tax refund check is officially ending. Starting with the 2025 tax year, the agency will transition nearly all disbursements to direct deposit, a move intended to boost efficiency, cut costs, and reduce fraud.

On the surface, the data supports the decision. During the last filing season, about 94 percent of individual taxpayers voluntarily provided their bank information for a direct deposit. Treasury checks are reportedly 16 times more likely to be lost, stolen, or otherwise compromised than electronic payments. From a purely operational standpoint, eliminating the IRS's paper-processing "kryptonite" looks like a clean, logical optimization. The system is moving toward the user majority.

But this is where the clean narrative breaks down. A system optimized for 94 percent of its users isn't necessarily a successful one, especially when that system is a core function of government. The real story isn't about the 94 percent who will barely notice the change; it's about the remaining six percent who will be directly impacted. This isn't just an operational tweak. It's the introduction of a systemic barrier for millions of the country's most vulnerable people.

The High Cost of Being an Outlier

Who makes up this six percent? We're talking about roughly 10 million individual taxpayers who receive paper checks for reasons that are anything but simple preference. This group isn't a monolith of technophobes; they are people constrained by circumstance.

The data paints a clear picture of the barriers. According to the FDIC's 2023 report, 4.2 percent of U.S. households—that’s around 5.6 million households—are unbanked. They have no checking or savings account, making direct deposit a physical impossibility. For these individuals, a paper check isn't an inconvenience; it's the only viable mechanism for receiving funds. Then there are Americans living abroad who face hurdles with international banking, religious communities like the Amish who hold sincere objections to electronic financial systems, and victims of domestic violence who cannot safely share bank account details.

The IRS plan treats these deeply rooted structural issues as a simple matter of non-compliance. The proposed solution for those who don’t provide bank details is a cascade of bureaucratic friction. First, the IRS will send a letter requesting the information. If the taxpayer doesn't respond or get an exception approved, their refund will be held for six weeks before a paper check is finally mailed. This six-week delay isn't an operational necessity; it's a penalty. It’s a punitive measure levied against people who are often the least equipped to absorb it.

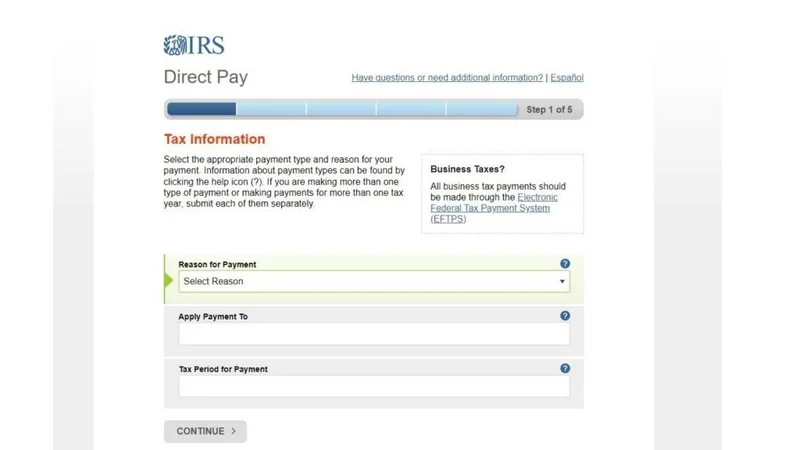

This is the part of the plan that I find genuinely puzzling. The IRS is attempting to solve a paper problem by creating a new, more complex paper-and-phone problem. The agency is swapping the low-friction, passive process of mailing a check for a high-friction, active process requiring taxpayers to navigate letters, online portals, and phone calls. How does adding these failure-prone steps actually increase overall system efficiency? What is the projected cost, both in dollars and in public trust, of managing the inevitable confusion and delays this will cause for 10 million people?

A System Designed for Failure

The proposed exception process itself seems engineered for dysfunction. The plan involves a dedicated phone line for taxpayers to call and request an exception. Yet, the fact sheet notes that, for security reasons, IRS telephone assistors "will not be permitted to receive taxpayers’ bank account and routing information during the call."

Let that sink in. The primary channel for resolving the issue—a taxpayer calling to provide their information—is explicitly designed to prevent the resolution of that issue. This is a workflow that would be laughed out of any private-sector operations meeting. It forces taxpayers who may lack reliable internet access or digital literacy back to online portals or paper forms, reintroducing the very friction the system claims to be eliminating. It’s like creating a fire department that is forbidden from using water.

This entire initiative is a classic example of what happens when a complex human system is viewed through a simplistic quantitative lens. The goal is to eliminate paper, but the execution guarantees more letters, more calls to already-strained phone lines, and more desperate taxpayers caught in limbo. It reminds me of a software update that runs perfectly on 94% of devices but completely bricks the remaining 6%. In the tech world, that’s not a success; it's a catastrophic product failure requiring an immediate rollback. Yet, in this case, it's being presented as progress.

The timing of this mandate also intersects with a volatile information environment. We’ve already seen viral misinformation about fictitious "$1,390 IRS Relief Payments" spreading across social media. This demonstrates a public primed for confusion about IRS disbursements. Introducing a deliberately punitive delay and a convoluted exception process is practically an invitation for bad actors to exploit the uncertainty. A taxpayer panicking over a six-week delay is a taxpayer vulnerable to scams.

While stakeholder groups like the American Bar Association and the Taxpayer Advocate Service are pushing for sensible solutions—like Treasury-issued debit cards or expanded access to low-barrier accounts—these are still just recommendations. The current, official plan relies on a system of letters and phone calls that seems destined to fail the very people it’s supposed to accommodate. Progress shouldn't punish the vulnerable. This isn't modernization; it's the weaponization of inconvenience.

An Efficiency Mirage

The IRS is chasing a laudable goal with a deeply flawed map. The agency is set to discover that the marginal efficiency gained from eliminating paper checks for the compliant majority will be completely swamped by the immense operational, financial, and human cost of managing the exceptions. This isn't a step toward a sleek, modern tax system. It's an administrative nightmare in the making, built on the assumption that anyone not conforming to the digital mean is a problem to be solved rather than a citizen to be served. The numbers on the spreadsheet may look good today, but the real-world data from next year’s filing season will tell a very different story.