Article Directory

A Cosmic Opportunity Meets Bureaucratic Paralysis: The 3I/ATLAS Data Gap

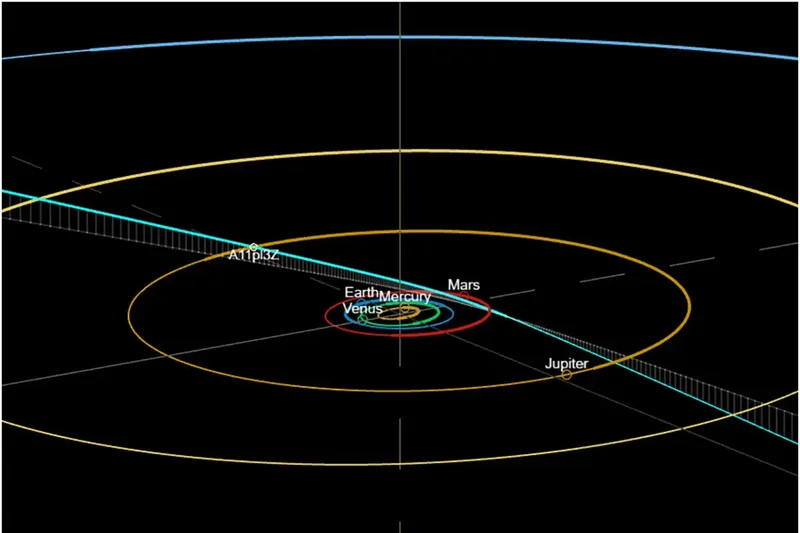

An object designated Comet 3I/ATLAS, the third interstellar visitor ever detected, just made its closest approach to Mars. On October 3, 2025, it passed within 29 million kilometers of the Red Planet, presenting an unprecedented opportunity for observation. This object is an outlier—at least a thousand times more massive than its predecessors, `Oumuamua and Borisov. Its trajectory is a statistical anomaly, aligning with the ecliptic plane and timed for close passes with multiple planets.

For any data-driven analyst, this is the equivalent of a black swan event appearing on the horizon. It’s a moment where a single, high-quality data set could fundamentally alter our understanding of the universe. The central question, as framed by Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, is binary: is 3I/ATLAS a product of nature, or is it a product of intelligence? The answer, we were told, was waiting for us in the data streams from a fleet of orbital assets currently circling Mars.

But as the object made its flyby, the primary Earth-based institution responsible for collecting that data was, for all practical purposes, closed for business. A US government shutdown has resulted in the furlough of 83% of NASA’s federal workforce. That’s more than 15,000 employees. The timing is, to put it mildly, suboptimal.

The Promise of the Payload

The array of instruments currently pointed at 3I/ATLAS represents a formidable data-gathering apparatus. NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter carries the HiRISE camera, which was expected to capture images with a spatial resolution of 30 kilometers per pixel—the highest-resolution data we could possibly get. This data point alone could constrain the diameter of the object's nucleus, currently estimated to be larger than five kilometers.

Then there are the European Space Agency’s assets. The Mars Express orbiter, with its HRSC camera and OMEGA spectrometer, was positioned to gather imaging and spectroscopic data. The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter was tasked with producing color images and composition analysis. Add to that NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft for UV spectroscopy, plus instruments from China’s Tianwen-1 and the UAE’s Hope Orbiter. I've looked at hundreds of mission prospectuses and corporate capital expenditure plans, and the sheer density of observational power being focused on a single, transient event is staggering. This isn't just taking a picture; it's a multi-spectrum, multi-platform interrogation of an unknown.

The data from these instruments is supposed to be the arbiter. It would allow us to analyze the chemical composition of the gas plume surrounding 3I/ATLAS, determine its size and shape with greater precision, and look for any anomalies that defy natural explanation. The probability of an interstellar object this large, on this particular path, at this particular time is exceedingly low (Loeb puts the combined likelihood at around 0.00001, or 1 in 100,000). The data from Mars is the only way to determine if this is a winning lottery ticket from nature or something else entirely.

The problem is that data doesn't analyze itself. Raw telemetry from deep space isn't a JPEG that appears on a screen. It requires a complex pipeline of processing, calibration, and interpretation run by specialists. And most of those specialists are currently at home.

A Terrestrial Anomaly

While a fleet of billion-dollar instruments performed their duties flawlessly millions of miles away, their human support network on Earth was kneecapped by political gridlock. This introduces a critical, unquantified lag into the entire process. The current `3I/ATLAS news` isn't about discovery; it's about delay.

So far, the only visual evidence we have from the flyby is a faint smudge. An astrophotographer, Simeon Schmauß, painstakingly stacked publicly available images from the Perseverance rover’s Mastcam-Z camera to reveal a blurry hint of the object where it was predicted to be. This is a commendable piece of citizen science, but it’s also a damning indictment of the situation. We are relying on an enthusiast’s reprocessing of non-specialized camera data because the official, high-resolution pipeline is clogged.

This is like trying to analyze a company’s quarterly performance based on satellite photos of its parking lot because the CFO has been locked out of the office during the earnings call. The core financial data exists on a server somewhere, but the people who can access, verify, and explain it are unavailable. The market is left to speculate based on incomplete, anecdotal evidence.

The shutdown creates an information vacuum. How long will it take for the furloughed teams to get back to work, clear the backlog, and process the 3I/ATLAS data? Will priority be given to this specific observation, or will it fall into a queue behind other mission-critical tasks? Details on the internal triage process at NASA remain scarce, but the operational impact is clear. Every day of delay increases the risk of misinterpretation as public speculation rushes to fill the void. The object is traveling at about 130,000 mph—or to be more exact, its hyperbolic escape trajectory means it isn't coming back. Our window to collect and analyze data in near-real-time is closing.

The Real Variable Is Us

Ultimately, the story of 3I/ATLAS has become less about a mysterious object in the sky and more about the operational readiness of our own institutions. The most significant risk factor in this extraordinary scientific opportunity isn't a technical failure or an act of God; it's a procedural, entirely self-inflicted paralysis. We have a front-row seat to a cosmic event, and we've chosen this moment to argue about the budget. The data is out there, waiting. But the final, most unpredictable variable in this celestial equation appears to be human bureaucracy.